RESISTANCE & RESILIENCE

In 2001, UNESCO proclaimed the Music, Language, and Dance of the Garifuna as an *Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity*. This recognition was granted to the Garifuna Nation, an Indigenous and Afro-descendant people who, barely two centuries prior, faced genocide and the potential erasure of their culture from global knowledge.

Who Are the Garifuna?

The ancestors of the Garifuna were present in the Caribbean long before Columbus’s arrival. By tracing their lineage to the Arawaks and Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles, the Garifuna are undeniably Indigenous to the region. To be Indigenous to the Caribbean means having lived here for millennia, contributing to the region’s cultural richness by blending with other races that later arrived. Discussing Caribbean Indigenous identity necessitates examining its origins and continuity.

In the book *The Rise and Fall of the Black Caribs*, Earle Kirby and C.I. Martin note:

“The recorded history [of St. Vincent] begins with the arrival of Columbus in the West Indies. However, the island was already inhabited by a large community of Indigenous Kalinago (Caribs) and Arawaks, believed to have migrated from Venezuela, their original home being the Orinoco Basin. Europeans, on their arrival, found that St. Vincent contained far more Caribs than any other island.”

French priest Père Labat described St. Vincent as “the centre of the Carib Republic—the place where the savages are most numerous.”

At the time, St. Vincent was not the only Caribbean island occupied by Indigenous peoples. From Trinidad in the south to Jamaica in the Greater Antilles, islands were home to groups such as the Taino, Arawaks, Lakono, and Kalinago (Caribs). However, only on St. Vincent did the Kalinago intermix with African escaped slaves, forming a distinct, hybrid people called *Black Caribs* by Europeans but known by their Indigenous name, *Garifuna*. Père Labat commented:

“I don’t know what has induced them [the Caribs] to receive these Negroes among themselves and to regard them as belonging to one and the same nation.”

The Garifuna adopted the language and cultural practices of the Indigenous Kalinago, evolving into a distinct people. Today, of all the Indigenous groups encountered by Europeans in the Caribbean during the 16th century, only the Garifuna endure as living representatives of their culture and community. The question remains: *Why?*

Resistance and Survival

One explanation is that on St. Vincent, known as *Yurumein*, the Garifuna identified and operated as a nation, which was recognised by European colonisers. After fierce resistance to European settlement and land claims culminated in the First Carib War (1772–1773), the British signed a treaty with Garifuna chiefs. This treaty—a rare acknowledgement of an Indigenous nation by a colonial power—validated the Garifuna’s existence as a distinct entity.

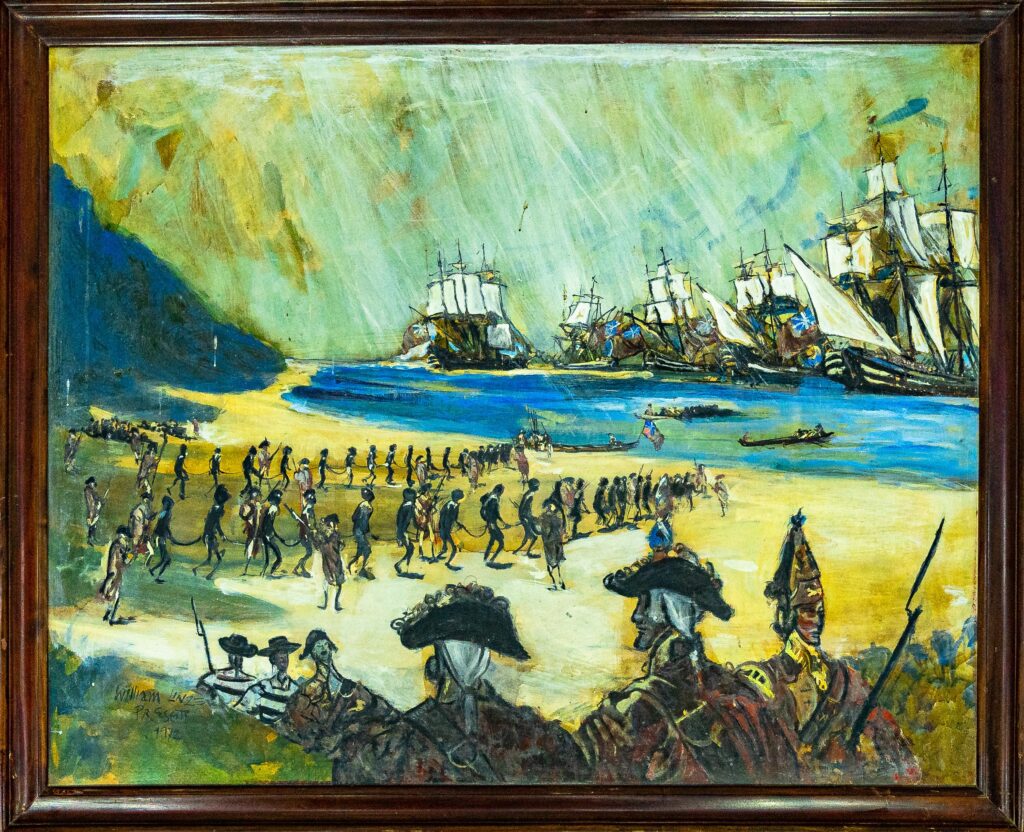

However, their determined resistance to British encroachment on St. Vincent ultimately led to their defeat following the death of Paramount Chief Joseph Chatoyer in 1795. In 1797, the British deported 2,248 Garifuna from Balliceaux to Roatán, an island now part of Honduras. From there, the Garifuna spread across Central America, establishing significant communities in Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, Guatemala, and beyond, including the United States.

Identity and Resilience

In the 1980s, the Garifuna rejected the colonial term *Black Carib*, formally adopting *Garifuna* to affirm their identity as part of the African Diaspora while also embracing their Indigenous roots. This dual identity allows the Garifuna to maintain a unique cultural position while engaging with the broader Afro-descendant movement.

Despite over two centuries since their forced exile, the Garifuna have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Today, their global population is estimated at 300,000, and their language, music, cuisine, spiritual practices, and traditions remain vibrant. The Garifuna maintain cohesion as a nation despite residing across multiple political borders in Central America.

The Garifuna language serves as a unifying force, transcending the official Spanish and English languages of the countries where they live. The Garifuna flag, with its black, yellow, and white stripes symbolising African heritage, Amerindian roots, and peace, respectively, is a powerful emblem of their unity and enduring spirit.

The Garifuna story is a testament to the strength of cultural resistance and resilience in the face of adversity.